DIVING IN THE MOON:

HONORING STORY, FACILITATING HEALING

Talking to Strangers

© Dan Yashinsky

Many summers ago we were strolling on a path by a lake when a man walked by. Our three-year-old son asked if we knew him and we said, no, he was a stranger. Then he piped up: “We don’t know any strangers, do we?” We had to agree that, no, we didn’t know any strangers. But his question stayed with me. It’s true that if you know someone, they’re not strangers any more. But what about all of the people out there, unknown or not-yet-known, who may one day walk towards us on a path by a lake, or on a city street? How do we welcome – or at least acknowledge – those who will visit our world from the vast and mysterious Land of Strangers? The old courtesies that taught us how to treat strangers have eroded. We no longer remember, for example, why it’s important to share bread and salt with a stranger. In the old stories, and still in some places around the world, you offer a cup of tea before you even ask a stranger’s name. In our society, you can “like” a “friend” on a social media network, you can feel “linked in” to people you’ll never meet, you can conduct all manner of business with people you never actually talk to. Who’s a stranger anymore, if you can have a thousand “friends,” each one “liking” you enough to send you the latest picture of their cat? Could it be that we have enough “friends” nowadays? Maybe it’s time to start a movement to bring back strangers, and the customs that help us welcome them?

In my house, when we put out an extra glass of wine for Elijah at the Passover dinner, I often think about the strangers in – or on the borders of – our lives. According to legend, Elijah never appears as a saint or prophet bearing blessings. Instead, he shows up in the form of a beggar, a homeless vagabond, an impoverished stranger. That same son, age seven and a good listener to the stories he’d grown up with, walked by a panhandler in front of the drugstore on St. Clair Avenue West and asked, “Daddy, is that Elijah the Prophet?” “Could be,” I told him as we put our usual quarter in the cup. At that year’s seder, we told the story about a man who wanted to see Elijah’s face. He spent his childhood and youth staring at the extra goblet of wine, hoping that Elijah would appear; but it never happened. He complained to the rabbi, who told him there was a guaranteed way to see the face of Elijah. He was to go to the poorest family in the village, and bring the best of food and the best of wine to their Passover celebration. Then, surely, Elijah would appear to him. He did as the rabbi recommended. It was a magnificent, joyous, delicious, and completely unexpected celebration, and the poor family was thrilled and grateful. But still no Elijah. When he went back to the rabbi, disappointed yet again, the rabbi handed him a mirror, and said, “Look at the mirror. You were the face of Elijah the Prophet to that poor family.”

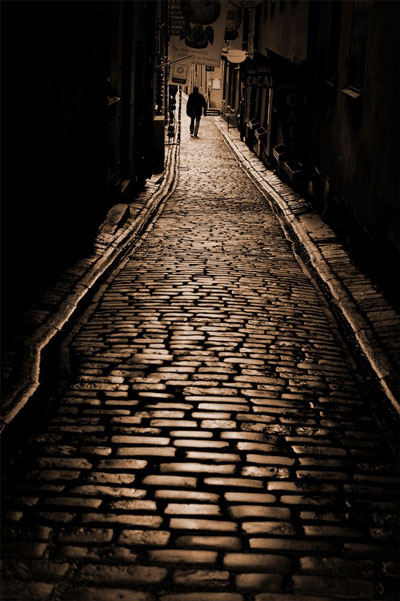

I was walking down Spadina Road in Toronto one early evening when I was rudely accosted by two strangers. I had just come from the swimming pool at the Miles Nadal Jewish Community Centre and was clutching a little black swim bag. Coming towards me on the sidewalk were two big men, very drunk. I had a feeling there might be trouble, and there was. As I tried walking by, one of them stood in my way and said, “Get out of the way, you little Jew!”

I was walking down Spadina Road in Toronto one early evening when I was rudely accosted by two strangers. I had just come from the swimming pool at the Miles Nadal Jewish Community Centre and was clutching a little black swim bag. Coming towards me on the sidewalk were two big men, very drunk. I had a feeling there might be trouble, and there was. As I tried walking by, one of them stood in my way and said, “Get out of the way, you little Jew!”

This gave me a real dilemma. You see, I am a little Jew. I wasn’t offended by the name, since it happened to be true. But I don’t like being bullied. I learned this from my Romanian grandfather. When he was a little boy, the local bully taught him a bad word and told him he should say it to his mother. It was a set-up. The bully didn’t mention that it was one of those words you should never, under any circumstances, say to your mother. His mother was shocked and appalled, and sent him on to his father. When he heard the bad word, his father slapped him. My five-year-old grandfather, ever vigilant to the finer points of social justice, pointed out that it was the bully who’d taught it to him, and he didn’t even know it was one of Those Words. Then his wise dad told him that the slap wasn’t for him, it was for the bully. My grandpa ran outside and passed the slap on to the bully, and the kid never bothered him again. I’m not recommending this as a surefire way to deal with your neighborhood bullies, but it worked for my grandfather.

Remembering this story, I knew I had to do something. I turned on the sidewalk and called out: “Hey!” They stopped and turned. I, little Jew that I am, walked up to them. I couldn’t think of anything particularly heroic, noble, or edifying to say by way of repartee, so I just said: “Don’t talk to strangers!” They mumbled, “Sorry, man …” and shuffled away.

A rabbi once asked his student how he would know that the light of dawn had come. The student answered, “When you can tell the difference between an olive tree and a walnut tree?” Good answer, but no. “When you can tell the difference between a dog and a goat?” No. Then the rabbi explained, “It is when you can look on the face of a stranger and see the face of your brother or sister. That is when you will know daylight has finally come.”

Maybe what I should have told the two men on Spadina Road was: Don’t talk to strangers, unless it is to offer some bread and salt, or invite them for a cup of tea. Then take a good look at their face, just to see if they look like your brother or sister.

Dan Yashinsky is a storyteller and the author of Suddenly They Heard Footsteps – Storytelling for the Twenty-first Century, and the recently-published Swimming with Chaucer – A Storyteller’s Logbook. He founded the Toronto Storytelling Festival in l979, and 1001 Friday Nights of Storytelling in l978. He currently works as the storyteller-in-residence at Toronto’s Baycrest Centre for Geriatric Care. www.tellery.com E-mail:

Dan Yashinsky is a storyteller and the author of Suddenly They Heard Footsteps – Storytelling for the Twenty-first Century, and the recently-published Swimming with Chaucer – A Storyteller’s Logbook. He founded the Toronto Storytelling Festival in l979, and 1001 Friday Nights of Storytelling in l978. He currently works as the storyteller-in-residence at Toronto’s Baycrest Centre for Geriatric Care. www.tellery.com E-mail: