Story Kin & Cousin #7: Storytelling to Connect Across Time

with Alton Chung and Angela Juhl Davidson

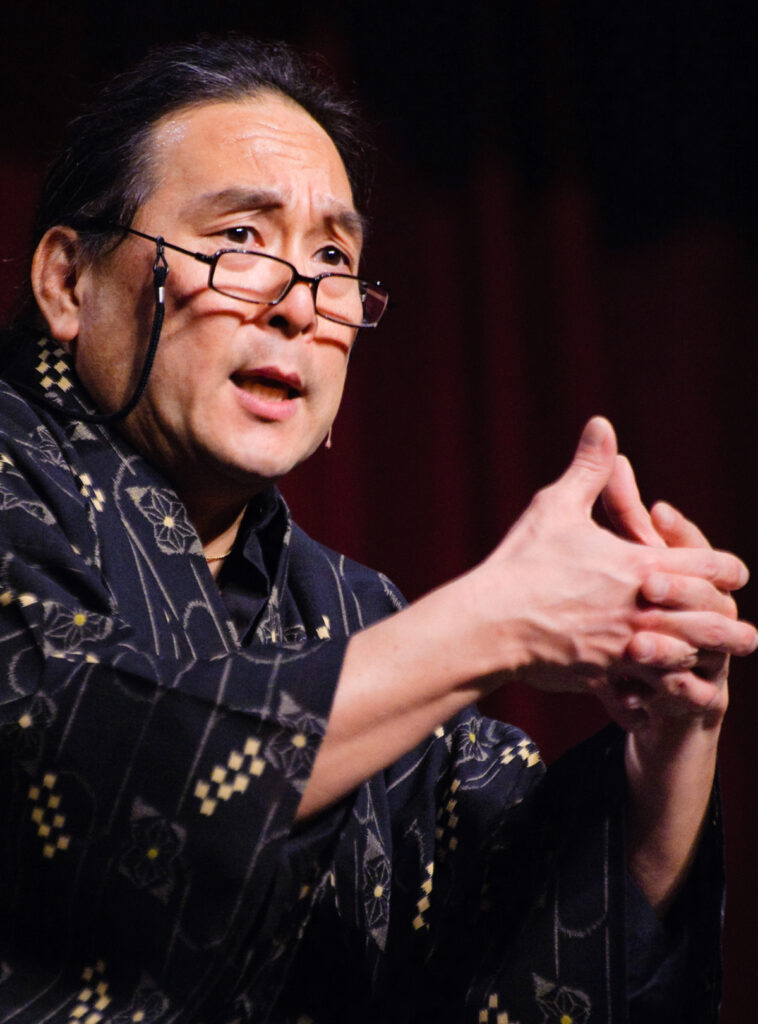

Welcome to our seventh Story Kin and Cousin Conversation! We continue the vision of the Story NOW! interviews by exploring the power of storytelling to transcend divisions and create change. We interview an oral storyteller and a cousin storyteller from a kindred art form. Join us for a conversation with Storyteller Alton Takiyama-Chung, and Story Cousin, artist and writer Angela Juhl Davidson.

Vel: What was one of the first stories that caught your interest? Who told it to you?

Alton: The first stories I ever heard were my mother telling me Japanese folktales. The first time I went to the National Storytelling Festival in 2003, I’d just become a professional storyteller, I heard Jay O’Callahan. I was sitting in the back of the tent, and then, all of a sudden, he launched this story. And when he closed the story, I realized I had been sitting there for thirty minutes at the edge of my seat, barely breathing, and I had been somewhere else. Another amazing piece was when I was at the last StoryFest, the last big storytelling festival in Seattle in 2004, and I heard Carmen Agra Deedy. This woman in a polkadot dress got up there, and she started telling a story about how she loved fire trucks. And the whole tent, we were just hysterically laughing, and agreeing, and identifying with this person. Again, I realized: this is incredible, this medium, this storytelling thing. I need to learn more. This is the level of excellence I would like to attain. That was my real awakening, realizing the possibilities, and the power of stories.

Angela: I remember my father telling me this story that I didn’t know at the time, but now know is the narrative of the Croglin Grange Vampire, who is this entity that was first written about 1890, and sort of got folded into Varney the Vampire stories in the 1920’s. I very specifically remember my father quite often telling me this story before bed as a child. That was my first storytelling experience. Though for me there were other tales heard on the schoolyard, I grew up in Napa, California, and we have an extremely local cryptid called the Rebob that doesn’t exist anywhere else. It’s sort of this flying monkey thing, and it’s very localized to this one street. It’s up on Patrick’s Road, which is near this cemetery that people refer to as “the pioneer cemetery,” but it’s just this local, little family cemetery. I remember hearing stories about the Rebob, and understanding this was something deeper and more long-lasting than just some story my friends were telling me, because my mom told me she remembered growing up in the ‘70s and hearing about the Rebobs, and they lived on the same street. That’s when I started realizing how connecting stories are, how they connect across time, and that there’s something deeper about them.

Vel: Painting with spoken words or pigment on paper, what’s needed to make a story visible?

Angela: For me, it’s a sense of play. I have different processes, because sometimes I start with an idea of what I want to paint: maybe a figure from folklore, maybe a certain spirit. I spend a lot of time playing with concept sketches. I love texture. I feel texture adds to mood, and it’s something I’ve always loved. I love mineral watercolors that separate and granulate, they’re great for experimenting with textures. A lot of times as I’m working on a sketch, I’ll be playing around with different color palettes, and whether I want to do pencil undersketches with watercolor over, which is something that Maurice Sendak did with Where the Wild Things Are, or whether I want to work with something that provides a stronger sense of line, like water-safe pen with watercolor. If I know the concept, that’s the kind of play that goes into it. But then there’s other paintings where I don’t know where it’s going. That’s the joy of watercolor. If you want to work with it, in all its possibility, you have to let it go where it wants to go. Oftentimes I’ll create things where I’m just placing blots of paint on the paper and create a story around it later, after it’s expressed itself. Watercolor pigments swirl and spread on wet paper and it can be very interesting. It’s all play for me. Additionally, I should mention that one aspect of the work I put on instagram is that for each piece of art I try to write a kind of “micro-story”- there isn’t a full fledged plot arch, it’s more a mood, a set of images perhaps, that says something about the painting or its subject. I didn’t always do this when I started, and indeed I’m pretty new to all of this, but I’ve found that when I include a written story with a painting people react, and interact, a lot more fully, they emphasize with characters in the painting and for me that’s when I can see that it’s visible to them.

Alton: For me, making the invisible visible, I’m painting with words, and any story has to be real for me, so I can make it real for the audience. As I’m writing the story, as I’m creating the story, as I’m telling the story to myself and to others, I’m building a motion picture in my mind. I’m seeing the images, and describing it to the audience. The analogy I would say, would be like the benshi. In the plantation days in Hawaii, there’s a guy named a benshi. He would bring a silent movie to the plantations, and everyone would pay a dime, or whatever it is, to go watch this movie. And he would be the voice of the actors, and he would be the narrator, as well as the sound effects man. While everyone’s watching the silent movie, he’d be creating the dialogue, being the different characters. That’s how I see how when I create things: I’m the narrator, I’m the actor, I’m the special effects person, and all that is real. I’m watching this movie in my mind’s eye, and narrating to the audience, embodying the story. Letting them know this is what I’m seeing, this is real for me, and trying to make it as real for them.

Vel: Both of you are imaginative, but interested in tradition and technique. How do you balance the two?

Alton: Certainly it depends upon the type of story you’re telling. If it’s a personal story or tall tale, then creativity just takes over. But when you’re looking for that dynamic tension, that balance between creativity and tradition, I think that’s mostly seen, for me anyway, when I tell folktales to people. Within a folktale are the norms and nuances of a culture from which that folktale is taken, as well as the cultural specific attitudes and motivations of the characters. All of that has to be preserved if you want to have authenticity. And yet, the story also needs to resonate with the audience, right? So the creativity part comes in when we start painting the scenes and embodying the characters in ways the audience can immediately identify with them. Being creative within the structure of a tale while trying to maintain the cultural authenticity, that’s the tension, the dynamic balance, where those two things come together and need to exist.

Angela: I often work with ghost stories, with scary stories, and with the darker side of things. Having focused on Gothic Literature through most of my MA, I’m always interested in the anxieties that help form a tale. For instance, I’m fascinated by stories about sleep paralysis and what they call “Old Hag Syndrome,” where supposedly people are waking up unable to breath and find it’s because an old woman is sitting on their chest . It’s a phenomenon often connected in folklore studies to the succubus and the incubus. Anyway, I recently did a piece where it was important to balance thinking about anxiety and thinking about agency, and some of the issues bound up in these original tales and accounts while also trying to find ways to make them resonate, so the story wasn’t just about this terrifying older woman sleeping on your chest. I wanted to take this character who was about suppressing agency, and give her the agency to choose differently, to escape the paradigm these tales seem to force her into. That’s the creative part, the part that’s about trying to find room for characters , especially those that have become sources of fear in traditional tales, to move. For me, I have to start with: what are the anxieties and what are the concerns that formed these tales?

Vel: Can you recall one story where research was an essential part of crafting?

Angela: One of the interesting things about being somebody who creates art on Instagram is there’s a lot of synergy, and a lot of drawing challenges. You have these themed events, and there’s these micro areas of artists that focus on folklore and folktales. There’s a Folktale Week, there’s Folktober, where all of October there’s different folklore-related prompts every day–it’s mostly scary folklore. Most recently it was Faebruary, where there were thirteen days of fairy folklore related prompts. I ran into something I had never encountered before, which is this idea of Machine Elves. It’s the idea of these creatures that are encountered by a certain number of people during DMT trips. So I went down this rabbit hole for most of a day, reading about the ethnobotanist, Terence McKenna, who had made machine elves prominent in his work, and reading about what people supposedly experienced, reading criticism of this supposed theory. That’s one of the things I really love: learning about new stories, new entities. It’s an interesting world, creating art on Instagram.

Alton: Any historic tale I tell is grounded in massive amounts of research, and also subject to constant revision as new facts are uncovered. Historical stories I tell, by definition, are going to be wrong. Case in point: the story of the 442nd Combat Regiment, the all-Japanese combat regiment in World War II, one of the most highly decorated units in US military history. Amazing bravery. I wasn’t there. And even if I were, I can’t know everything going on everywhere. Like the saving of the Lost Battalion in the Vosges Mountains in Eastern France. I have to rely on the accounts of others and do historical research. The story has to change as our understanding of the facts change. Case in point: the medal count. Distinguished Service Crosses were elevated to Medals of Honor in 2000. There were about 20 of them elevated. Originally, I started off stating the sheer number of awards: about 18,000 individual awards. When I got down to Distinguished Service Crosses, which is the second highest medal you can get for valor in combat, I said there were like 52, and 21 Medals of Honor. A historian veteran afterwards came up to me and said: “That’s not quite right. Once a Distinguished Service cross is elevated to the Medal of Honor, they just become Medals of Honor. It’s actually 32, Distinguished Service Crosses, and 21 Medals of Honor.” I didn’t know that. Let me change that in the story. I try to minimize that kind of discrepancy by doing as much research as I possibly can. Yet, you still come across items that are disputed. As the person presenting this, I don’t want to take sides. I say; “Some people said this, some people said that. This is what the result was.” As far as my favorite sources for research: firsthand accounts and interviews for historical pieces are prime. Pre-Covid days, I’d go to libraries. Nowadays, with Covid, the internet is what I try to do, but I go back to primary sources. Going back to primary sources, people who were actually there, their firsthand accounts, that’s gold. Because they were there, they lived it, they’re expressing their emotions, and that is that feeling of intimacy I would like to bring to the stories.

Vel: Angela, where do you like to go for your sources?

Angela: Firsthand accounts and interviews where I can find recordings of them. It’s a little different for me, because I don’t think what I do has the same gravity as what Alton is working with. I don’t think it’s quite the same level, when I’m trying to research people’s experiences with Machine Elves. I would probably feel a lot more pressure if I was working with more historicized events, but I love first hand accounts, as well. There’s a lot of great databases I have access to as well, as I am also taking classes in Library Science courses. There’s great publications on both storytelling and folklore and I tend to spend a lot of time on Jstor.

Vel: Both of you are drawn to ghost stories. What do you find most compelling about them?

Alton: Growing up I was terrified of ghost stories. Every time someone told me a ghost story, I imagined it to be real. That terrified me. I didn’t want to hear them. When I became a storyteller, I realized that, growing up, everyone had ghost stories in Hawaii:“things happened to me” or “this happened to a friend of mine.” People would sit there and exchange ghost stories. But I wasn’t hearing that anymore. I realized that was a slice of life that no longer exists. That’s where I got started. Because I was sharing a part of my experience, with others, to a time which doesn’t exist anymore. The stories that are not being heard, or told about maybe in other venues, but I wasn’t hearing them. Now I am fascinated with them. They represent, to me, things science cannot explain–yet. Sort of like what electricity was to people in the 1600’s. What I find compelling about them is, it gives me hope: that there is something beyond death, and there is possibly a chance for redemption. It opens up the realm of possibilities: things we don’t understand, we don’t quite know how it works yet. I find that intriguing. We get little bits and crumbs from different stories, and people have different experiences. Until we can get to the point where we can understand and prove what’s going on, it’s in that just out of reach realm. And it borders on the realm of imagination and fantasy. And yet, I believe it’s just a matter of time before technology can allow us to explain and experiment and prove that this is what’s going on.

Angela: I love that answer. I like what you said, Alton, about the unexplained. I think that’s similarly why people are into cryptids. There’s something so compelling about the idea that we don’t know it all. I’ve always been interested in ghost stories, because I don’t have a strong sense of what comes next, or if anything does come next, so I love the idea that there’s a shadow or a stain. I always love ghost stories where it almost feels like something repeats like a groove on a record. One thing I’ve noticed, sharing my art, and usually I do create small stories for the artwork I create, is people seem to be attracted to ghosts and cryptids, because they almost identify with them, feeling that they are similarly misunderstood. That’s something I didn’t realize until sharing with other people. People seem to be attracted to the idea of the misunderstood ghost, the misunderstood cryptid, whether it’s the Mothman or a Rebob, or whatever it is. Because people feel there’s a part of themselves that others don’t connect with, and won’t be understood.

Vel: What questions do you have for each other?

Angela: What I’m really interested in, Alton, is your process. When you’re developing a story, what are the physical manifestations of it? I’ve mostly done academic research. I’m curious if your process looks similar? Especially with firsthand accounts. The nuance is what’s so hard. The words are simple. I’d like to hear more about that.

Alton: Are we speaking of historical research or ghost stories or folktales? Angela: I imagine it varies quite a bit. I’ll say: historical.

Alton: Normally for historic tales, I’ll try and get the lay of the land. For example, I just spent an inordinate amount of time putting together a story of the Filipino veterans of World War II. I did a lot of basic research. What is the historical truth I can come up with? What were they promised? How were these rights and privileges taken away? Has this situation ever been resolved? That’s a basic baseline. Luckily, I had an interview with a Filipino veteran who gave me parts of the story. His own experiences, and his own feelings growing up through that time. I was contracted by this group interested in the legal ramifications and modern day resolution, or near resolution. I had to fill in gaps, try and put in the pieces. What was the chronology? What did Roosevelt promise these Filipino veterans to fight the Japanese in the Philippines? Trying to understand firsthand accounts of what it was like to be ill-equipped and fighting a guerilla war, essentially, for several years. How did the United States renege on their agreements, and basically leave these people with nothing? The legal fights, culminating in the awarding of the congressional gold medal in 2017. By then, most of these people are in their 80’s and 90’s. The majority of them passed away without getting anything. Again, addressing the larger question of: how to get to the heart of the story? Finding firsthand accounts for all these different pieces. The heroes afterwards fighting to restore some rights and privileges and recognition. That’s what the veterans really wanted, recognition. You can’t tell the whole thing, that becomes a historical novel. What are the key pieces which can be seen through the eyes of one person? Seeing through the eyes of this one veteran I knew, who I interviewed, I could see what’s going on. Creating the narrative, being conscious of the chronology and staying true to the historic facts. A lot of moving parts. Again, keeping your eye on: what is the gift I want to give the audience? How do I stay true to that throughout the long narrative? And being true to the heart of the story. So, my question to you: have you ever collaborated with a storyteller on a project? In such collaborations, the teller gets to tell the story. What does an artist get out of taking on such a project?

Angela: Working with a living storyteller is definitely something that would really excite me, but I haven’t quite had that opportunity yet.

Alton: What would that kind of collaborative process look like? Do you need to have a story first? What does the feedback between the artists look like?

Angela: I think, a lot of storyboarding. I definitely would prefer the story first to have a sense of where their thought process is. And then, as I mentioned earlier, doing a lot of storyboarding, doing a lot of things to fix composition. Looking at textures, looking at colors, and seeing where the storyteller’s ideas and mine might meet. So it’s something that bounces back and forth. I think the hardest thing is getting on the same page with something like that.

Alton: How does that feedback process work? You storyboard it, you create something, you show it to the artist, the artist says,“Ok, this is what needs to be changed…” What is the best way to get that communication across?

Angela: In this case, I would think of it more as my trying to get the storyteller’s thoughts across. I’m someone who can work in a lot of different moods, who can work in a lot of different color palettes, so getting some of that down first. Make sure I know what they’re thinking, and when I give them information about what I’m thinking, we’re working together.

Alton: When you storyboard a story, there’s lots of little panels. So I guess, when creating something like this, how many pieces of art do you need to go and convey the story?

Angela: In children’s book illustrations there’s storybooks and there are picturebooks. With a storybook, you have text, and you’re illustrating in a way that’s very literal. With a picturebook it’s more of a synergy between words and image. So it’s figuring out: is this more of a storybook, where I’m just illustrating words, or is this a picturebook? How much of my own ideas should be added? Is it going to be minimal text, and then the picture is going to tell a big part of the story? Those are two different processes.

Alton: One sounds like you’re following the other artist, and one sounds like it’s more collaborative. What would you prefer?

Angela: I really enjoy the idea of picturebooks, where there is a lot put into it that was not with the original text. The interesting thing is, the issue of illustrator agency comes up frequently when I’ve taken classes about writing and illustrating picturebooks. Often the writer of a picturebook wants to include massive amounts of cumbersome notes to tell the picturebook illustrator what to do, and that’s just not how the process works unless you’re a rare author/illustrator. So I think it’s really about establishing early on whether we’re equal collaborators, or I’m illustrating your words. It’s really important. For the most part, if you’re talking about something that’s formatted like a picturebook, it’s going to be a pretty equal collaboration. Speaking of how stories form, I’m so interested in the firsthand accounts: have you ever struggled when dealing with a story with multiple points of view? Which point of views to privilege? Or issues where it was hard to put the perspectives together in a way that told a cohesive story?

Alton: No one person who has seen everything or been everywhere. One of the devices I use is, I create a fictional narrator. He doesn’t exist, but everything that comes out of his mouth is from a firsthand account; someone experienced this. She or he becomes the omnipotent narrator. An amalgamation character. But everything, the descriptions, the dialogue even, comes from firsthand accounts. That’s how I craft the narrative: picking specific incidents I know historically happened, and descriptions of what actually happened. With ghost stories, oftentimes there will be a firsthand account of one person’s experience. I’ll do additional research to find similar things, historic facts, or legends about a specific area where this haunting occurred. I can step out of the character, become the narrator, and say: “Here’s additional information he doesn’t know, but I know. One hundred years ago, this is what happened…” The ghost stories I like to create are: a person has a weird experience, here’s the background story, here’s how we think they are connected. There’s firsthand accounts where something scary happened, we don’t know what it was, we ran away. It was scary, it was interesting, but something’s missing for me. I’ve been authorized by Dr. Glen Grant’s estate to tell all of his ghost stories. Dr. Glen Grant collected the weird stories of Hawaii for over thirty years. One of his favorite stories was the story of one state park, on the big island of Hawaii, where a family was kept up by ghosts. They found these markers off the parking lot, things chiseled into the rock, they couldn’t read. These pools of mists coiling there, at the base of these two stone monoliths, go up and disappear. Dr. Grant finds out later the locals call this place Obake Park, Ghost Park. You’ve got to put food on the graves, otherwise they’re going to keep you up all night long. I told this story in Okinawa one Halloween. After the story this guy comes up to me, he says: “I know the real story behind that story.” His uncle was part of the construction crew that built that park, and in grading it, they found there are Hawaiian burials there. He tells me the backstory of what happened, why this haunting occurs, and why the place is still haunted today.

Vel: Any upcoming projects or events you’d like to share?

Angela: I’m in the process of learning how to share my stories with people digitally, and building my portfolio of children’s illustrations, and learning all sorts of things about how to incorporate 3D elements. If you’re interested in following that, find me on Instagram.

Alton: March 24th I’m going to be part of the Six Feet Apart Anniversary Show, April 12th I have a concert with the Statewide Cultural Extension Program with the University of Hawaii, in a program I call “Myth-chief, Magic and an Ogre or Two,” a program of Asian folktales. May 15th, I’ll be performing with the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, a virtual show: I’ll be telling a story of the picture brides from Hawaii. May 16th, I’ll be a guest on Karen Chace’s Story Cafe; it’s an interview show of her local cable access channel over in Massachusetts.

Vel: Is there one thing you’d like readers to take away from this conversation?

Alton: I would encourage tellers to explore collaborating with artists from other mediums to create something new, something different, something greater than the sum of the parts. I see potentially great synergy and creativity from this. A way to reach new audiences and stretch ourselves as artists. Be creative, take risks, and create something absolutely wonderful.

Angela: I’m not a person who could do what Alton does; I struggle to speak well on my feet. There are other ways to share stories. Storytelling is a medium that can happen in other ways if you are somebody who may struggle telling stories in a more traditional way. Explore different ways to connect with people through story, because they’re out there, and sometimes you find them in the strangest of places.

Alton Takiyama-Chung, a Japanese-Korean storyteller, grew up with the superstitions and the magic of the Hawaiian Islands and tells stories from Hawaii, Asian folktales, ghost stories, and historical tales like those of the Japanese-Americans in WWII. He performs across the USA and internationally and is also a former Chairman of the Board of Directors of the National Storytelling Network. Find Alton at these upcoming virtual shows in 2022: March 24th: Six Feet Apart Productions (SFAP) Anniversary Show; April 12th:“Myth-Chief, Magic an an Ogre or Two” at University of Hawaii; May 15th: Asian Art Museum of San Francisco; May 16th: Karen Chace’s Story Cafe. Visit https://www.altonchung.com/ or get in touch at

Angela Juhl Davidson is a watercolorist, writer, and multi-medium creative. Her writing has appeared in the Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies and in the journal of the International Society for Contemporary Legend Research (ISCLR). She has an MA in English Literature, focused on the Gothic, and is studying Library Science and Children’s Book Illustration. She and her art haunt Instagram under the username the_autumn_gloaming. For more from Angela follow her at https://www.instagram.com/the_autumn_gloaming/ or get in touch at