DIVING IN THE MOON:

HONORING STORY, FACILITATING HEALING

Answering the Call to Adventure:

A Hero’s Journey Group for People Facing Life-Changing Illness and Disability

© Jennifer Lunden LCSW, LADC, CCS

The artist is meant to put the objects of this world together in such a way that through them you will experience that light, that radiance which is the light of our consciousness and which all things both hide and, when properly looked upon, reveal. The hero journey is one of the universal patterns through which that radiance shows brightly. What I think is that a good life is one hero journey after another. Over and over again, you are called to the realm of adventure, you are called to new horizons. Each time, there is the same problem: do I dare? And then if you do dare, the dangers are there, and the help also, and the fulfillment or the fiasco. There’s always the possibility of a fiasco. But there’s also the possibility of bliss.

– Joseph Campbell

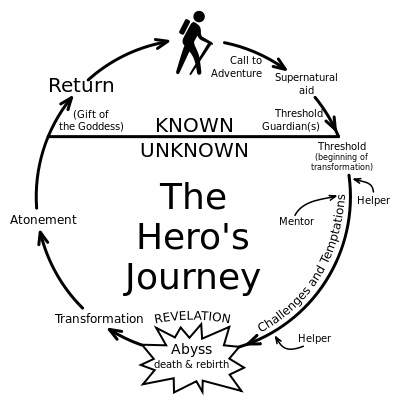

I had been chronically ill for over twenty years, and a therapist for seven, when I came up with a brilliant plan. I would form a therapeutic writing and storytelling group for people struggling with life-changing illness and disability, and frame it around the idea of the hero’s journey. The only problem was—I didn’t know a thing about the hero’s journey. But I was pretty sure that I was on one, and that anyone facing a life-changing illness or disability might be challenged to reframe their experience through that lens. So I started cramming.

You might say this was my Call to Adventure.

DEPARTURE

Supernatural Aid:

Supernatural Aid:

I bought a copy of Joseph Campbell’s book, The Hero With a Thousand Faces. If anybody was an expert on the hero’s journey, I figured it was Joseph Campbell. He studied myths from around the world his entire career. He wrote The Hero With a Thousand Faces when he came to see that all cultures share some key themes when it comes to the archetypal story of the hero’s journey. He called it the monomyth.

I roped my colleague, David Bigelow, LADC, into joining me. We had previously co-facilitated a therapeutic writing group that used Erik Erikson’s stages of development to help men with addiction histories to more closely examine their life stories. We decided that our Hero’s Journey group would run twelve sessions, and found five willing participants with illnesses or disabilities ranging from diabetes to Lyme disease, asthma, chronic fatigue syndrome, osteoarthritis, multiple chemical sensitivity and brain damage resulting from a stroke. A number of the participants struggled with more than one diagnosis, and most also faced co-occurring depression. Some were also in recovery from addictions.

David was fascinated by The Hero With a Thousand Faces, and offered to take on the task of synopsizing each theme we would address in group. In retrospect, I realized that David was the Supernatural Aid on my hero’s journey with the group. He would provide the special tools I needed to make it through to the other side. The book was our amulet.

The Crossing of the First Threshold:

I started with a story. I told the group about Jean-Dominique Bauby, who suddenly lost the use of every muscle in his body except for his left eye, a victim of “locked-in syndrome” at just 43. Amazingly, Bauby went on to write an entire memoir by blinking his eye in code. He called his memoir The Diving Bell and the Butterfly because even though he was completely immobile—locked into his body as though it were a diving bell—he had not lost his imagination, and it freed him.

I explained to the group that in addition to the hero’s journey each of us was on as we faced our own illnesses and disabilities, we, as a group, would also be embarking on a metanarrative of the hero’s journey, and that David and I were on it too. I warned them that as a group we might go through some challenging times, and said that in some ways it was like we were in a dark wood, and none of us knew the path, but David and I had a map and a compass, and we would all find it together.

INITIATION

The Road of Trials:

Each week, David and I collected key quotes from the book, and added some writing prompts, and handed them out to the group. Then, based on the previous week’s assignment, group members shared the pieces they had written about their lives. Then David talked for a little while about the next phase of the hero’s journey.

On our first day, our session was framed around the Call to Adventure. One of the questions in our handout asked, “Was there a ‘herald’? Who, or what, was it? What did your herald look like? How did he/she/it herald the changes to come?” Barbara wrote about the doctor who diagnosed her osteoarthritis, and how this diagnosis compelled her to begin to adjust her thinking and accept that chronic pain would be her lifelong companion.

For another session, we wrote, “Joseph Campbell says that each of us has a ‘spiritual double,’ an external soul not afflicted by the losses and injuries of the present body, but existing safely in some place removed. Have you ever had a sense of connection with your ‘spiritual double’? If you could commune with your ‘spiritual double,’ what would that be like? What might your ‘spiritual double’ remind you about yourself?”

This question led to a rich discussion about our higher powers, and some members of our group talked about how they felt betrayed and abandoned by theirs, who left them to suffer so in their bodies. Grace (names changed to protect confidentiality) was moved to write a dialogue with her higher power, and when she brought her script in to group, Barbara volunteered to read aloud the part of her higher power while Grace read the part of her more human, hurting self. After they had read, I suggested they switch parts, so that Grace could read the part of her own higher power. She noted a sense of expansiveness after reading both parts.

Things were going along fine, I thought. People were sharing their stories, expressing their feelings, reframing their struggles, and forming empathic bonds.

It was around the time of the Road of Trials, however, that I got a phone call. One of our members, Charleen, said the group wasn’t meeting her needs and she was thinking of leaving. I did not want her to leave the group, and I asked her to tell me more about how it was failing to meet her needs. She said she didn’t like the structure of the group, and would prefer if it were more open-ended.

David and I had put a lot of thought into the structure of the group, and I was a bit attached to following the design we had prepared. But I thought Charleen had something important to say, and that it was even possible that others in the group felt the same way. So I asked her if she would come back one more time, to see if her concerns might be shared by others. When she did, a space was created that opened the group up to share honest feelings, and, sure enough, I learned that there was some room for improvement. Members agreed it was our best session yet. I determined to listen to the needs of the group and to change it in a way that would work better for them, without letting go of the vision that I had when I formed the group in the first place.

So the next week, David and I crammed three units of information—the entire Initiation phase—into one, delivering all of this knowledge in a shorter time to leave more room for open dialogue. Quoting Campbell, David talked about the importance of approaching the journey with a “gentle heart.” But something wasn’t jiving. I wasn’t feeling connected to what was going on in the group that day. I wondered, was it was just me? But then Alan spoke up. He said he didn’t feel connected to what was going on in the group in that session. He burst into tears, describing his sense of isolation and “otherness.” This was a life-theme for him, but I had a feeling that he was not as alone as he thought, and checked with the group. Sure enough, none of us felt connected. We were all in agreement: the session had kinda sucked.

Apotheosis:

Apotheosis:

I went home and thought about it. I wondered what had happened and tried to figure out how to make sure it didn’t happen again. And thinking about it, I realized that our group had just gotten to the middle of the hero’s journey, right into the place where many of us were in our own individual journeys. The dark wood. No wonder we were befuddled. And when we spoke of the “gentle heart,” David and I skipped right over the Road of Trials — the struggles that were so integral to our illness experiences.

So we decided to throw our structure out the window and trust the organic process of the group. In the hero’s journey, this is called the Apotheosis, when, as the Wikipedia synopsis describes, “The hero’s ego is disintegrated in a breakthrough expansion of consciousness.” We invited the participants to use the additional time to share more of their own stories.

One day around that time, Morley, one of the group members, came to his individual session with a hunch in his shoulders and a downcast expression in his eyes. He told me that an old problem had come back. Morley had diabetes, and the complications had increased as he aged. He told me that five years previously, a fierce nausea swept into his life, and he was wracked with inexplicable daily vomiting. Doctors could not tell him what was happening to his body. It went on like this for two years, and it nearly drove him to suicide.

I listened to Morley’s story of his suffering, and felt that I alone could not adequately hold it for him. I invited him to tell the story of his nausea for the next session of the hero’s journey group, a few days away. I asked him to do his best to help us fully understand his experience.

On the day of the group, Morley told the harrowing tale of his nausea, and I noticed that all of us in that room were sitting on the edge of our seats. The empathy in the room was palpable. When his story was finished, Morley let out a big sigh and said, “Thank you. I feel so much better. I feel like a load has been lifted off my shoulders.”

This was hard for some of us to believe, I think. We wanted so much to fix it, to give him hope for a solution to this terrible specter that had returned to shadow over his life. If we could have handed him a magic potion, we would have.

Most of us fall into that trap of wanting to fix things. But sometimes things cannot easily be fixed. And sometimes, just listening with a full and open heart can help transform suffering into healing. When Morley was able to tell his story and those of us in the room were fully present to contain it, he was not alone.

The next week, he returned for an individual session after a weekend getaway, and his face was aglow. The week had flown by, he said. I asked about the nausea. Like the ocean tides, ruled by the enigmatic moon, just as mysteriously as it had returned, it had receded.

The Ultimate Boon:

As I listened to the group over those weeks, I began to discern certain themes that repeated themselves in our discussions: courage, doctors, families, and the therapeutic value of satire and dark humor. People were transforming their stories right before my very eyes. Barbara, who in her previous life had walked on fire, literally, taught us about the courage it takes just to reach for her cane every morning. Morley reclaimed his story when he showed us how a dehumanizing and demoralizing trip to “The Looney Bin” could be reconfigured as a satirical “fractured fairy tale” through which he could turn the tables of power and recover his sense of dignity. Hidden between the lines of a story she wrote about a boot, Grace unearthed some unacknowledged truths about her life. Alan shared an important revelation one day when he said that if he hadn’t had his stroke, “I would still be the controlling mess I used to be. And I’m no longer that person. So we can celebrate that. This is a new person. Yes, I have a disability. But I think I’m done with the pity party.”

Alan’s revelation led me to one of my own. I realized that my illness had made me fierce. I am fierce about fighting for my own growth and my own vision, and I am fierce about advocating for the other “dispossessed” people in the world, people who struggle like I once did and still, sometimes, do. Before I became one of “the dispossessed,” my beliefs were more philosophic; now I live them in the deepest parts of me.

RETURN

Refusal of the Return:

I have neglected to report how much we laughed in the group. Here we were, a group of people struggling with Lyme disease, osteoarthritis, multiple chemical sensitivity, diabetes, stroke, and depression, and we laughed more in two hours than I laughed all the rest of the week. We had built a true camaraderie, and I did not want the group to end. I tried in fact to stop it from ending by asking members if they would like to continue on through the next cycle. But half of them said no. They had gotten what they had needed and were ready to move on. I had to face the fact that this group would end.

Master of the Two Worlds:

And yet, this group—my first hero’s journey group—would never leave me. There was so much I knew I would always carry in my heart about this group. For instance, I know with certainty that there are things a group can do that I just can’t in individual counseling. There is a special magic to a group. Open hearts. Connection and camaraderie. In a supportive group, isolation withers away.

The group has its own wisdom, its own process, its own trajectory. I learned to trust the organic collective process of the group. My most important job as the facilitator is help to create a safe place for people to make their own journeys.

Freedom to Live:

In this last phase, according to the Wikipedia synopsis, “the hero bestows the boon to his fellow man.”

I began planning the next group. And I couldn’t wait to begin.

JENNIFER LUNDEN, LCSW, LADC, CCS, is a practicing mental health counselor and the founder and executive director of the Center for Creative Healing, which is located in Portland, Maine. She can be reached at . The agency’s website can be viewed at www.thecenterforcreativehealing.com

JENNIFER LUNDEN, LCSW, LADC, CCS, is a practicing mental health counselor and the founder and executive director of the Center for Creative Healing, which is located in Portland, Maine. She can be reached at . The agency’s website can be viewed at www.thecenterforcreativehealing.com