At the National Storytelling Network, our mission is to advance all forms of storytelling within the community through promotion, advocacy, and education.

STORY NOW! Interview Series

The theme of our 2019 annual conference was Story Now!

Now! From the boardroom to the classroom, and the page to the stage, personal stories and folktales are catalysts for change in every aspect of our lives.

Now! We are witnessing the power of stories to tear down the walls that divide us, build bridges between people and cultures, and connect us, human-to-human. In this interview series, we’ll talk to storytellers who exemplify this Story Now! movement.

Each month we’ll sit down with an NSN member or member organization, from around the globe, and go behind the scenes to explore how they are personally harnessing the power of storytelling to tear down walls, to be a catalyst for change and connect us human-to-human. Through one-on-one, in-depth conversations, we’ll discover the type of storytelling they do, how they do it, who their audience is, and, most important, they’ll give examples of the real world, tangible results they get.

Kathy Greenamyre is NSN’s Community Relations Manager. She will be conducting interviews and contributing content each month for our Story Now! Interview Series. Kathy is the owner of a video production company. She’s interviewed hundreds of people over the past 12+ years. Her passion is to discover the world (and maybe even learn how to fix it) by listening to, recording, and spreading personal stories.

Kathy Greenamyre is NSN’s Community Relations Manager. She will be conducting interviews and contributing content each month for our Story Now! Interview Series. Kathy is the owner of a video production company. She’s interviewed hundreds of people over the past 12+ years. Her passion is to discover the world (and maybe even learn how to fix it) by listening to, recording, and spreading personal stories.

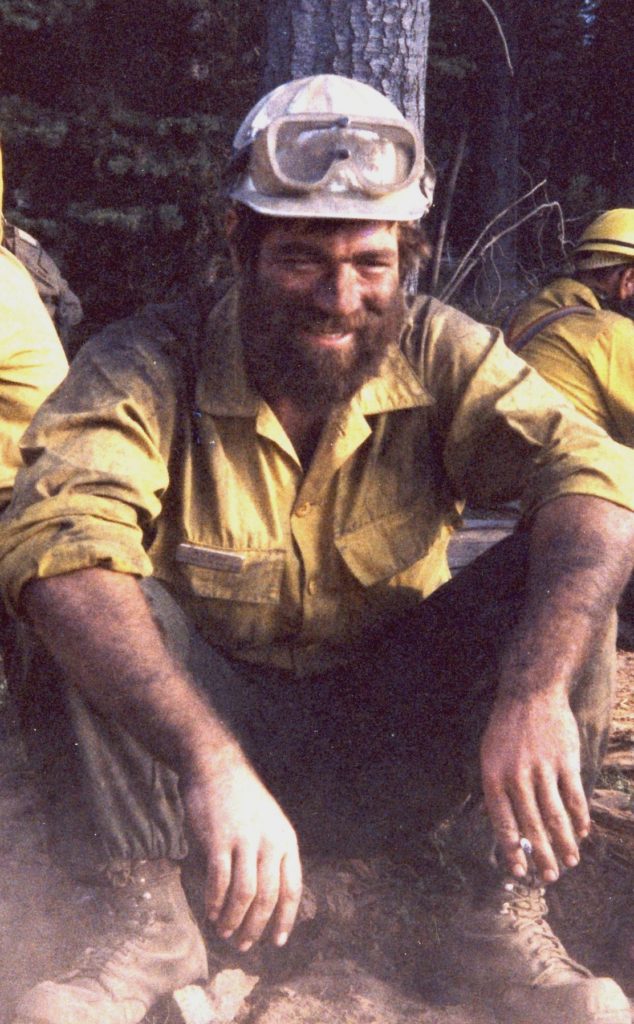

Pete Griffin – Juneau, Alaska

Alaska State Liaison for the National Storytelling Network

Kathy Greenamyre: Pete, you live in beautiful Juneau, Alaska and, as a retired naturalist, you have created a unique (and enviable) storytelling career for yourself where you get to do your story work on cruise ships!

In a bit, we’ll talk about the fascinating work you do on those ships.

You grew up in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula miles from the nearest small town. You didn’t have a lot of other kids to play with. You spent a lot of time wandering through the woods alone and exploring the lakeshore, looking at wildflowers, listening to birds singing from the top of the pine and spruce forest.

Later in this interview, you tell how those early years influenced the long career you would go on to have with the National Forest Service.

So, let’s start your story there. Tell us about your extraordinary career with the National Forest Service.

Pete Griffin: I began my 36-year career with the US Forest Service in Lower Michigan as a biological technician. My main jobs were to collect water samples from swimming beaches to test for fecal coliform to determine whether or not beaches should be closed for public safety.

I also test-netted lakes to sample fish populations and used electrofishing gear to establish size/length parameters and density of trout populations on streams. That led to being promoted to wildlife biologist where I reviewed and recommended ways to improve wildlife habitat.

I also test-netted lakes to sample fish populations and used electrofishing gear to establish size/length parameters and density of trout populations on streams. That led to being promoted to wildlife biologist where I reviewed and recommended ways to improve wildlife habitat.

Though that was very satisfying, I eventually began to feel a desire to influence management of national forests beyond my ability as a wildlife biologist in the field.

In one of the most difficult decisions I’d ever made in my career, I transferred from my home state of Michigan all the way to Minnesota!

KG: Describe what “influencing management of national forests” looked like once you moved to Minnesota.

PG: There I began to broaden my career experience to include management of campgrounds, trails, land use and acquisition, permitting of commercial activities on the national forest, archaeological resources, and responsibility for forest fire prevention and suppression, not to mention budgeting and supervision.

I transferred to Alaska, another jolt to the system, in order to gain still more experience, this time in the application of environmental laws and regulations in Forest Service planning documents and preparing responses to court cases.

KG: Wow, what a unique resume! What was the next step in your career?

PG: At the age of 47, despite the fact my career was no longer “on a fast track,” I was selected to be the Ranger (administrative head) of the Juneau Ranger District on the Tongass National Forest. This was a high-profile position in the state capital, one eagerly sought by other employees with thoughts of advancement in the agency. It was known to have political benefits along with political pitfalls.

PG: At the age of 47, despite the fact my career was no longer “on a fast track,” I was selected to be the Ranger (administrative head) of the Juneau Ranger District on the Tongass National Forest. This was a high-profile position in the state capital, one eagerly sought by other employees with thoughts of advancement in the agency. It was known to have political benefits along with political pitfalls.

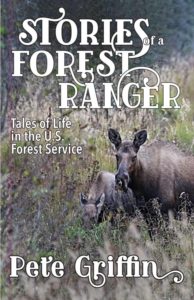

My eleven years in Juneau provided a number of stories that became the core of my recently published “Stories of a Forest Ranger” (Parkhurst Brothers Publishers).

KG: Talk about how you launched your storytelling work after your retirement from the Forest Service.

PG: When I retired in June 2010, I knew that retirement wasn’t just the end of having to go to work every day. It was going to be a new life… and I had to do something to take the place of work. Yes, I could go fishing more often, but I was already catching more fish than the family could eat. I could go hunting more frequently, but dividing a moose between the members of  our hunting party gave us as much as we could eat in a year.

our hunting party gave us as much as we could eat in a year.

I knew storytelling was something I wanted to explore more. Shortly after retiring, I performed a “fringe” show at the 2010 NSN Conference in LA. I was nervous. I’d never before told Forest Service career stories to an audience that did not know me beforehand. I got some great feedback.

KG: So, at this point in your story you’ve recently retired and the next thing you know you are working on cruise ships as a storyteller and nature guide! How in the world did you land that gig?

PG: I received a call from a former employee Ron, Director of the Mendenhall Glacier Visitor Center. He asked me if he could pass my name and contact information to Disney Cruises.

PG: I received a call from a former employee Ron, Director of the Mendenhall Glacier Visitor Center. He asked me if he could pass my name and contact information to Disney Cruises.

Disney was preparing for its first time ever cruises to  Southeast Alaska in 2011. They wanted names of authentic Alaskan naturalists, local people who knew the animals, the whales, and the glaciers on their cruises.

Southeast Alaska in 2011. They wanted names of authentic Alaskan naturalists, local people who knew the animals, the whales, and the glaciers on their cruises.

I had done a popular, five-year series natural history essays on public radio, in addition to on-screen video promotions of the Tongass National Forest. Ron thought of me immediately.

Disney wanted three hour-long presentations on-stage in a theater that seated 1000. Gulp. Doing an hour-long natural history show was unimaginable, but I said yes. I wanted to see if I could measure up to Disney standards of entertainment, not to mention that I’d been enthralled with the Disney television programs, especially the nature shows, while growing up.

Disney wanted three hour-long presentations on-stage in a theater that seated 1000. Gulp. Doing an hour-long natural history show was unimaginable, but I said yes. I wanted to see if I could measure up to Disney standards of entertainment, not to mention that I’d been enthralled with the Disney television programs, especially the nature shows, while growing up.

I signed up for four week-long cruises in the 2011 season. The ship began its seven-day tours out of Vancouver, BC. Each trip stopped in Juneau where the naturalists boarded. They stayed aboard until the ship once again docked in Juneau, where they would disembark and a new naturalist would board for his or her week.

Disney did not pay me, but I was allowed to bring three guests who would enjoy a Disney cruise while I worked.

KG: Describe the type of presentations you gave.

PG: My Powerpoint presentations from the stage used photographs and science fact, blended with my personal stories of my Alaska experience.

They were well received and I used feedback from passengers and crew to improve my presentations.

I learned a lot about timing in my presentations and just how critical it was to adhere to a 50-minute time slot.

KG: I understand another high-profile cruise line contacted you to work for them.

PG: I received a call from Princess’ Entertainment Service Manager. He asked if I would be interested in being an “Enrichment Presenter” on Princess Cruises doing my “Living off the Land in Alaska.” If so, he offered me eight cruises in 2015.

KG: What an exciting offer! So, did you take the job with Princess?

I was interested in comparing Princess cruises with Disney cruises. I said yes but, this was in late spring 2015 and my summer schedule was set. I could comfortably squeeze in only two Princess cruises. But then he told me how much I would be paid for each cruise. Holly smokes! Princess paid their presenters? I immediately reviewed my calendar and squeezed in two more Princess cruises without canceling any other obligations.

Princess flew me to wherever their cruise was originating. I would give my presentation at sea in a 900-seat theater, and two to three days later, I would disembark when the ship docked in Juneau.

I found that Princess employed full-time naturalists on their ships. I took in all their programs sitting in the audience, noting what worked and what did not work. I tagged along when they were on deck with passengers pointing out whales and glaciers and sea otters. That arrangement worked for several years.

KG: And then in 2019, you received yet another exciting offer from that same cruise line. Tell us about it.

PG: In June 2019 Princess was in desperate need of a naturalist on the Sun Princess that was nearing the end of its world cruise with its Japanese clientele. They wanted a naturalist on the bridge to narrate the ship’s passages of Alaska’s Disenchantment Bay and College Fiord to view tidewater glaciers. I had some trepidation in agreeing to this assignment.

I’d never worked with a translator before, as I would be on the bridge of the ship. What if the food served on the ship was all Japanese? What if they didn’t have silverware? I had a difficult time with chopsticks. But I went. It was great.

KG: Describe your experience working with the translator.

PG: I worked with Keiko, a translator who taught English at a Japanese high school. Ahead of time, I wrote out every fact I might use while looking at glaciers and gave Keiko a copy a day or two ahead of time so she was able to translate at her leisure.

The food was great. While heavy to fish, noodles, and rice, there was plenty of chicken and beef, and sweet desserts know no geographic or political boundaries! The signs on the ship, however, were all in Japanese. I was an outsider here. It was an interesting experience.

KG: I understand that you should be on a cruise right now, Pete. But the coronavirus had another plan for you, didn’t it?

PG: We agreed on one 12-day cruise and five consecutive week-long cruises in 2020. I looked forward to the Summer of 2020. Alas!

KG: Why is storytelling so important to you?

PG: My goals for telling stories based on natural history or living in Alaska are two-fold. I want to entertain and I want to educate. “Edu-tainment” is a phrase I come across frequently. Perhaps my goals are three-fold. I try to convince folks that most of what they see on the Alaska reality television programs so popular these days bear little to no resemblance to actual life in Alaska!

KG: Who is your typical audience for your natural history stories?

PG: Audiences vary. My library audiences want to learn about plants and animals while being entertained. My cruise ship audiences want to be entertained while learning something about Alaska. When some of my listeners ask me more about one of my topics, I believe I’ve succeeded.

Sometimes people pose questions to me that I’ve never encountered before. That often causes me to do additional research in order to answer the question. I’ve come to understand that teaching is a great way to learn new things.

KG: Given your vast knowledge of nature, when you and I spoke by phone to prepare for this interview, I asked you if you talk about environmental issues that are on everyone’s mind, and what people can do to help save the planet — and you said that you don’t. Why not?

PG: Some folks believe my audiences put me in the perfect place to lecture about global warming, to convince people they have a moral responsibility to do something to reverse the terrible effects that loom large in our future. I don’t go there.

I don’t go there for a couple of reasons. The first is that telling a good story is enough. People need to absorb what they’ve heard, relate it to their own experience, and develop their own conclusions. They will then own those ideas that grew from the seeds of my stories.

KG: Say a little more about that philosophy.

Telling a story with an obvious moral and following it up by telling the audience what the moral is and what they need to do is heavy handed. To me that only works with the “faithful.” My audiences are filled with people whose beliefs range from global climate change is a hoax to those who believe global climate change is leading to doomsday.

Telling a story with an obvious moral and following it up by telling the audience what the moral is and what they need to do is heavy handed. To me that only works with the “faithful.” My audiences are filled with people whose beliefs range from global climate change is a hoax to those who believe global climate change is leading to doomsday.

KG: What are some of the facts about our natural world that you do feel comfortable discussing?

PG: The glaciers are receding. They have been for 250 years since the end of the “Little Ice Age.” The recession is accelerating. Harbor seals birth their pups on the ice floes in front of the tidewater glaciers and that allows the seals to escape predators on land, including bears and wolves.

I pose questions. What happens to the seals when tidewater glaciers recede above the level of the ocean? That may be bad for the seals but would it be good for the bears and wolves? Would that be bad for the orcas that prey on adult seals in the open ocean?

KG: So how does the audience react when you pose these questions in such an interesting way?

PG: Audience feedback is precious. I had told a story about the Mack Lake Fire. A young man had lost his life fighting that fire which was originally set to create habitat for an endangered species. I end the story wondering if saving a species from extinction is worth a human life.

Two weeks later, I received an email from a friend who had attended a storytelling event with his 12-year old son. They were on a walk through the woods when his son had asked him if saving a species from extinction was worth a human life. “That your story caused a 12-year old to ponder that question is a testament to the power of your story.”

Pete’s early years…

KG: Take us back to your upbringing. What was it like?

PG: I grew up in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula always, it seemed, several miles from the nearest small town. There weren’t a lot of other kids to play with in my pre-school years. I spent a lot of time wandering through the woods alone and exploring the lake shore, looking at wild flowers, listening to birds singing from the top of the pine and spruce forest.

“Alone but never lonely” …

According to adults familiar with the situation, I often claimed I wasn’t alone but accompanied by two friends that lived in an apple crate under a tree at the end of the road. Imaginary friends? I didn’t know what that meant. I might have been alone, but I was never lonely.

As I grew older, I began to think about a career where I could work in the woods by myself and never have to talk to another person all day long. A close neighbor was a conservation officer, a “game warden,” whose job it was to enforce hunting and fishing regulations. In high school I talked to him about what I needed to get into a career like his.

After putting some thought into it, I came to two conclusions. The first was that I didn’t have the right personality for law enforcement (I’d just as soon not talk to people) and that I wouldn’t be very good at it.

The second conclusion was that members of my extensive family were some of the first people I would have to cite for violation of game laws, particularly for shooting deer out of season.

Our small towns were populated with people living on the fringes of poverty. Poaching deer year ‘round to feed families was common place. No, being a game warden wasn’t a job for me.

KG: To pursue the career you wanted, what steps did you take to get there?

PG: In 1970, I earned a full-tuition scholarship to Lake Superior State College located only 35 miles away from home. There I obtained a bachelor of science in biology, which would eventually qualify me for jobs in the fields of wildlife or fisheries biology.

I had begun working summers for the US Forest Service in Lower Michigan in 1973, and I was able to continue temporary summer employment for two additional years before being hired on as a full-time employee, first as a technician and then as a wildlife biologist.

I finally had my job in the woods where I could be alone and rarely had to talk to another person all day long, alone but never lonely.

When I was hired by the US Forest Service, I was part of a wave of new hires in the agency. New laws had been passed that mandated federal agencies plan and analyze their projects. They were to disclose effects of those projects on endangered species, wildlife, fish, and recreation. The Forest Service was being forced to change.

I was one of the new guys. I joined an organization run by foresters and engineers. It took some time to adjust to overcome the resentment between the two factions: those who were trying to “save” the Forest Service by changing the way it did things, and those who were trying to “save” the Forest Service by reserving its traditions and culture.

When I complained about the tens of thousands of acres of pine plantations, he had countered by saying, “Pete, pines were the only thing that would grow in this sand. And that’s all there was. Just blowing sand where there used to be big red and white pines before the fires.” I realized that I had disparaged the efforts of this man I was working with.

Today tree planting is being considered world wide as a means of slowing desertification such as the southern advance of the Sahara Desert. Tree planting is being considered as a means of recapturing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

Efforts to establish forests are being hampered, however, by millions of people still dependent on wood for cooking. It’s a complex problem in a world far more complex than I’d ever envisioned back when I thought I knew all the answers.

KG: Can you give examples of stories and experiences in your work that changed you? Changed the way you thought?

PG: One source of stories I’ve found are those times when reality has collided with my view of the world and I’ve had to revise how I look at that world. When I was a new employee and knew everything, it was easy to judge the way programs were being run. I gave advice. I didn’t have to put that advice into action.

In the late 1970s, I was very critical of the Forest Service’s program for creating habitat for Kirtland’s warbler, an endangered species. Making habitat required that we clear cut large swaths of mature jack pine through commercial timber sales and a year later, burn the clear cuts to create the kind of habitat the warblers would next in.

We were falling behind in habitat goals. I was critical because I knew the Forest Service’s “heart” wasn’t into it. There were always excuses being made. There were only 300 Kirtland’s warblers left in the world. It was going extinct.

But one day, when everything seemed just perfect, the Forest Service began burning the 200-acre Crane Lake Unit. But several things went terribly wrong. The fire escaped, and in one short afternoon, burned 25,000 acres of forest in a horrific crown fire, destroyed 44 homes, and took the life of young firefighter Jim Swiderski… my friend, Jim.

In any story of the hero’s journey, the transformation of the hero is what is important. Those stories that transformed the way I look at the world are the ones that are my best stories, whether they are from my youth (“My Last Snake”) or my US Forest Service career (“Mack Lake Fire”).

KG: Any final thoughts and words of wisdom to leave us with, Pete?

I’ve come into the world of storytelling in a non-traditional fashion. Many storytellers are steeped in the traditions of storytelling, perhaps beginning by reading picture books to children. They studied the fairy tales and the fables, the classics of the Brothers Grimm, the epics from all continents.

There is often a shorthand, a code, used by storytellers in discussing their craft. I recall one day in a workshop, the leader describing the plot of a tale she had crafted as being derived from “The Frog Prince.” “Ahhh,” said the audience, nodding in understanding.

I raised my hand. “I don’t know that story,” I said. That drew incredulous stares from the other participants. But the leader briefly described the plot for me, and we were able to continue with the workshop. I found it an interesting experience and maybe validation that I’m not like other storytellers (at least in my mind).

Stories are a way to pass along traditions and culture of an organization. I wish the US Forest Service had understood that when I joined in the 1970s. I’ve worked to record some of my stories in the hope that someone may find them useful one day.

The Mack Lake Fire story is one that I’ve recorded with a live audience as part of “Diary of a Forest Ranger” broadcast statewide in Alaska. I’d posted the video to a Forest Service employee Facebook page which generated an interview request from a pair of Forest Service historians who are collecting those kinds of stories.

Diary of a Forest Ranger video – Mack Lake Fire Story

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LglpaJvOUhU&t=1s

I heard about NSN in 2004, joined, and went to the National Conference in Bellingham. There I found other people who had an interest in organizational storytelling: Karen Deitz, Jo Tyler, Sara Armstrong, Molly Catron, and Peter Engstrom. I’ve been a member ever since and have missed only two conferences since then.

TO READ PETE’S FULL INTERVIEW click the link below (Pete goes more in-depth, giving us a history lesson — explaining decisions made and actions taken at the National Forest Service during his tenure there — decisions that affected the whole country then, and still do to this day).

CONTACT PETE:

CONTACT PETE:

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/the.storytelling.ranger

Webpage: https://www.thestorytellingranger.com/

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/pete-griffin-a47ba423/

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LglpaJvOUhU&t=1s

phone: (907) 789-1093

email:

mail: 8943 Tournure Street, Juneau, AK 99801

Pete Griffin

National Storytelling Network Alaska Liaison

Juneau, AK 99801

(907) 789-1093

NSN loves publishing items submitted by the storytelling community! If you’re interested in writing something for publication on the NSN website, newsletter, or Storytelling Magazine please contact the NSN office for more information.

Contact the National Storytelling Network

c/o Woodneath Library

c/o Woodneath Library

8900 N.E. Flintlock Road

Kansas City, MO 64157

Telephone: (800) 525-4514

Website: https://storynet.org

Email:

Find us on social media!

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/National-Storytelling-Network-217381542906/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/NSNStorytellers

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/nationalstorytellingnetwork

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCBedmDdaRi9N-4Hs-QeYNqw